Total knee replacement is one of the most successful procedures in all of medicine. In the majority of cases, it allows patients to have more active lives free of chronic knee pain. Over time, however, a knee replacement may fail for a number of reasons. When this occurs, the knee may become painful, swollen, stiff or unstable, making it difficult to perform your everyday activities. If your knee replacement fails, revision total knee replacement may be required. In this procedure, some or all of the parts of the original knee prosthesis are removed and replaced with new components.

Although both procedures have the same goal - to relieve pain and improve function - revision surgery is different as it is a longer, more complex procedure that requires extensive planning, and specialized implants and tools to achieve an optimal result.

orthoinfo.aaos.org

orthoinfo.aaos.org

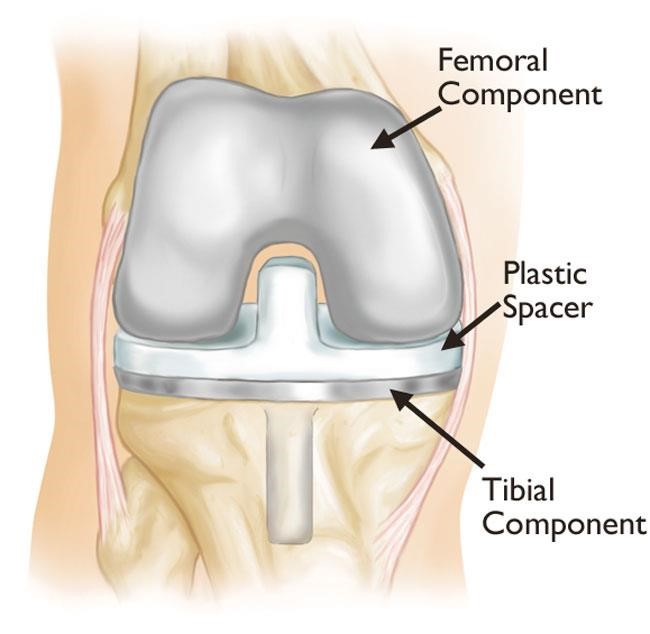

In a primary total knee replacement, the surfaces of the femur, tibia, and patella are replaced with a metal implant. (The patellar component is not shown here.)

Overview

During primary total knee replacement, the damaged knee joint is replaced with an implant, or prosthesis, made of metal and plastic components. Although most total knee replacements are very successful, over time problems such as implant wear and loosening may require a revision procedure to replace the original components, and sometimes the bone around the knee also needs to be rebuilt with augments (metal pieces that substitute for missing bone) or bone graft. Damage to the remaining bone usually makes it difficult to use standard total knee implants for revision knee replacement. In most cases, specialized implants with sleeves or cones and longer, thicker stems that fit deeper inside the bone are needed for extra mechanical support.

Indications for Revision Total Knee Replacement

Revision knee replacement surgery may be recommended if one or more of the following conditions are present:

Implant Loosening and Wear

For a total knee replacement to function properly, an implant must remain firmly attached to the bone. During the initial (primary replacement) surgery, the components were either cemented into position, or uncemented implants were used (these have special coatings that encourage bone to grow onto the surface of the metal to provide “biological” fixation) (A/Prof Woodgate routinely uses cemented implants in ALL primary knee replacements to ensure initial fixation). Over time, however, an implant may loosen from the underlying bone, resulting in knee symptoms such as pain, swelling or instability.

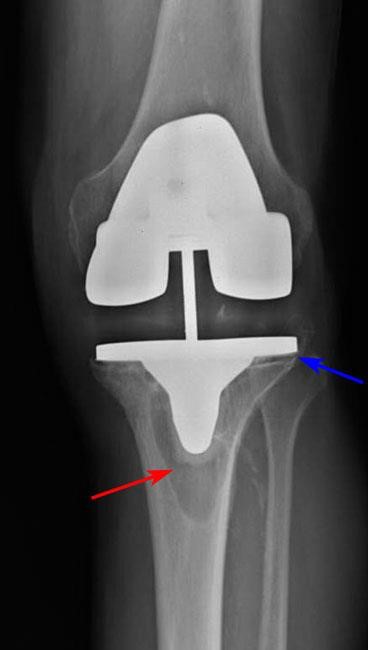

The cause of loosening is not always clear, but high-impact activities, excessive body weight, and wear of the plastic spacer between the two metal components of the implant are all factors that may contribute. Patients who are younger when they undergo the initial knee replacement may "outlive" the life expectancy of their artificial knee, and there is a higher long-term risk that revision surgery will be needed due to loosening or wear. In some cases, tiny particles that wear off the plastic tibial spacer accumulate around the joint and are attacked by the body's immune system. This immune response also attacks the healthy bone around the implant, leading to a condition called osteolysis. In osteolysis, the bone around the implant deteriorates, making the implant loose or mechanically unstable.

orthoinfo.aaos.org

Osteolysis (red arrow) has occurred around the tibial component, causing it to become loosened from the bone (blue arrow).

Infection in the prosthetic joint

Infection is a potential complication in any surgical procedure, including total knee replacement, with a reported incidence of 1-1.5%. Infection may occur while you are in the hospital or after you go home, and may even occur years later.

If an artificial joint becomes infected, it may become swollen, stiff and painful, as well as potentially causing other more generalised (systemic) upset such as fever or malaise. The implant may begin to lose its attachment to the bone, as the infection disrupts and destroys the interface junction between the implant or cement and bone. Even if the implant remains properly fixed to the bone, pain, swelling, and drainage/discharge from the infection may make revision surgery necessary.

Revision for infection can be managed in a number of ways, depending on the type or aggressiveness of the bacteria, the duration of infection, time since the original (index primary) knee replacement, general condition of the patient (particularly with regard to co-morbid conditions, which includes the ability to tolerate the anaesthesia for prolonged surgery), and patient preferences and expectations. Options can include:

- Debridement, Antibiotics, and Implant Retention (DAIR) - In some cases, the knee can be washed out and the inflamed lining removed to decrease the number of bacteria, the plastic modular tibial spacer can be exchanged, and the metal implants can be left in place, and the patient is maintained on longer-term antibiotic treatment (perhaps involving a combination antibiotics).

- One-stage Revision Surgery – In this technique, the infected implants are removed, the knee is thoroughly debrided and washed out to remove all signs of infection. A separate set of clean sterile instruments is then used to reimplant the new knee components.

- Two-staged Revision Surgery - In other cases, the implant is removed along with all infected material to treat the infection in the first stage surgery, and a temporary antibiotic-loaded cement spacer is placed in the knee. This spacer delivers high dose therapy locally within the knee joint cavity, and is supplemented with intravenous and/or oral antibiotic treatment for several weeks (typically 6 weeks). When the infection has been cleared, the second stage surgery is performed to remove the antibiotic spacer and insert the final knee prosthesis. In general, two-stage tends to yield a higher chance of curing the infection, but is associated with a longer recovery.

- Rarely, due to the patient being unfit for any surgery, antibiotic suppression alone is used.

Instability

If the ligaments around your knee replacement become damaged or improperly balanced (from trauma, inflammatory disease or other reasons), the knee may become unstable or unreliable. As most primary knee implants are designed to work with the patient's existing ligaments, any changes in those ligaments may prevent an implant from functioning properly. This may result in recurrent swelling and the sense that your knee is "giving way." If knee instability cannot be treated through nonsurgical means such as bracing and physiotherapy, revision surgery may be needed to add more constraint to the implants, to compensate for the ligament deficiency.

orthoinfo.aaos.org

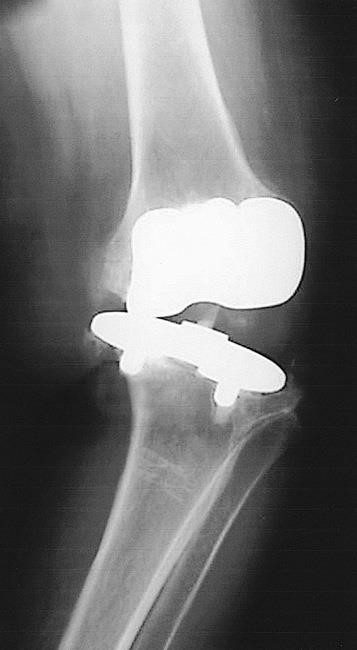

Injured ligaments can make the knee unstable.

Stiffness

Sometimes a total knee replacement may not help you achieve the range of motion that is needed to perform everyday activities. This may happen if excessive scar tissue has built up around the knee joint, a condition often referred to as arthrofibrosis. If this occurs early after the primary knee replacement, an attempt may be made to regain range with a "manipulation under anaesthesia” (MUA) – this usually is best done in the first 6 weeks after surgery.

If the knee remains stiff, or progressive stiffness develops over time due to extensive scar tissue formation or the position/sizing of the components in your knee limiting the range of motion, revision surgery may be needed.

Fractures (Periprosthetic)

A periprosthetic fracture is a broken bone that occurs around or adjacent to the components of a joint replacement. These fractures are most often the result of a fall, and usually require revision surgery, particularly if the implants are loosened by the trauma. In determining the extent of the revision needed, several factors are considered including the quality of the remaining bone, the type and location of the fracture, the type of the original implant (can fixation be achieved maintaining the implant), and whether the implant is loose. When the bone is shattered or weakened from osteoporosis, the damaged section of bone may need to be completely replaced with a larger bone-replacing revision component (also known as an endoprosthesis, megaprosthesis, or tumour prosthesis – even if no tumour is present).

Chronic progressive joint disease

This is typically seen in the scenario after unicompartmental knee replacement where the arthritis progresses in the remainder (non-resurfaced) parts of the knee.

Leg Length Discrepancy

It is usually stated that you cannot change the true length of a leg through a knee replacement, or revision knee replacement. However, if there is significant wear, bone loss, or knee angular deformity, correction of these through the new revision components may restore or straighten the leg closer to a more normal length.

Evaluation for Revision Total Knee Replacement

When a patient presents with a total knee replacement that is not performing well, due to pain, swelling, instability, stiffness, or other reason, it is important to obtain as much information as possible to determine the cause prior to undertaking under revision surgery.

A/Prof Woodgate will take a full history and perform a physical examination, particularly concentrating on the knee but also looking for other potential sources of symptoms (e.g. referred pain from the hip, back or pelvis).

Imaging tests will be needed including plain X-rays, which are used to identify the primary knee prosthetic components, alignment, any features suggestive of loosening or bone loss (osteolysis), possible ligamentous instability, fractures or swelling. Supplemental imaging studies may subsequently be ordered including CT scans (which can more closely assess bone quality and implant orientation and positioning) and MRI scans (usually requires a special sequencing software programme known as metal artefact reduction sequencing or MARS) which may demonstrate more clearly any soft tissue inflammation, features of infection, subtle fractures, and very rarely tumours. Nuclear medicine bone scans are often combined with white cell labelled scans or marrow scans if there is an index of suspicion that infection is the cause of knee symptoms.

Laboratory investigations are also required, not only as part of the general medical assessment but also to look for infection with blood tests showing elevation of the inflammatory markers (particularly the ESR and CRP). A knee aspiration can also be done to assess the type of cells in the knee fluid (elevated differential white cell count in infection) as well as sending the fluid to microbiology to culture any potential organisms (although cultures on aspirates often only identify the organism in about 60-65% of cases).

If a cause of the knee symptoms is clearly determined, and surgery is to proceed, A/Prof Woodgate will also obtain the original information from your previous surgical procedure, including copies of the old operation report and the knee implant inventory list. It is important for you to provide the information as to when and where the previous surgery was performed to expedite this process.

Risks and Complications

As with any major surgical procedure, there are risks associated with revision total knee replacement. The procedure is longer and more complex than primary total knee replacement, and has a greater risk of complications. Before your surgery, A/Prof Woodgate will discuss the risks with you and will take specific measures to help avoid any potential complications.

The possible risks and complications of revision total knee surgery include:

- Poor wound healing

- Reduced range of motion or stiffness in the knee

- Infection in the wound or the new prosthesis – While the reported rate of infection in primary knee replacement is 0.5-1.5%, the rate of deep infection in revision knee surgery is significantly higher, in the range of 4-10%. In view of this, antibiotic therapy will often continue for longer post-surgery to diminish this risk.

- Bleeding

- Blood clots (DVT) in the leg veins

- Pulmonary embolism—a blood clot in the lungs

- Damage to nerves or blood vessels

- Bone fracture during surgery

- Ligament injuries

- Prosthetic failure

- Patella (kneecap) dislocation

- Medical problems such as heart attack, lung complications, or stroke

Surgical Procedure

You will be admitted to the hospital on the day of surgery. Revision total knee replacement is more complex and takes longer to perform than primary total knee replacement. In most cases, the surgery takes from 2-3 hours.

The surgery is performed under spinal and general anaesthesia/sedation plus a femoral nerve sheath catheter block (with a Painbuster device). Following routine cleaning of the skin with antiseptic solution, sterile drapes are applied. The line of the incision made during your primary total knee replacement is utilised to expose the knee joint, though the wound incision may be longer than the original to allow the old components to be removed. The patella (kneecap) and tendons are mobilised and moved aside to reveal your knee joint. Specimens for microbiology and histopathology are taken from multiple soft tissues sites around the knee to exclude infection (the histopathology can involve frozen section analysis which is completed in about 15 minutes, and with accuracy of about 98% with regards to diagnosis or exclusion of infection). The metal and/or plastic parts of the primary knee prosthesis are assessed to determine which parts have become worn or loose or shifted out of position, and this should confirm the pre-operative diagnosis. The original implant(s) are very carefully removed to preserve as much bone as possible. If cement had been used in the primary total knee replacement, this is also removed. Assuming infection has been excluded by the pre-operative and intra-operative tests, preparation of the bone surfaces for the revision implant is undertaken. In some cases, there may be significant bone loss around the knee, and if this occurs, metal augments or platform blocks can be added to make up for the bony deficit, or bone graft material may be used to help rebuild the knee. The graft may come from your own bone (autograft) or from a donor (allograft). Finally, the specialized revision implant components are inserted and secured (these can either be cemented or uncemented), any surrounding soft tissues that are damaged are repaired, and the knee is carefully assessed for motion, ligament balance and tracking. A drain may be placed in your knee to collect any fluid or blood that may remain after surgery. The wound is then closed in layers. Sterile pressure dressings are applied from your toes to the upper thigh. After surgery, the anaesthetic is reversed and you will be transferred to the recovery room, where you will remain for several hours for close monitoring. After your condition is confirmed to be stable, you will be taken to your hospital room.

For simple revision total knee replacement (such as conversion from a failed unicompartmental knee), A/Prof Woodgate uses the RBK High Flexion Modular Knee system ( Global Orthopaedic Technology). For the majority of the remainder of the more complex knee revision procedures, either the S-ROM/MBT Rotating Hinge or the LPS implants (Deputy/Synthes) are used.

Post-Operative Care and Recovery

Most patients will stay in hospital for 3-7 days post knee revision surgery. Recovery from revision surgery is typically slower than after the primary knee replacement, though the type of in-hospital care is very similar, including:

- Pain Management – As well as the Painbuster femoral sheath catheter delivering local anaesthetic for approximately 48 hours, you will also be given regular Paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and for the first 48-72 hours, a PCA (Patient Controlled Analgesia) pump to deliver on-demand opioids (narcotic). After the drip is removed, the PCA will cease and oral narcotics (such as Targin and Endone) will be added.

- Physical Therapy – This is initially supervised exercises with the physiotherapist, as well as your own self-initiated exercises, with the goal of restoring range of motion and strength.

- Blood Clot Prevention – This includes graduated long compression (TED) stockings, inflatable calf compressors, and blood thinning agents (such as Clexane injections). Foot and ankle movements are also encouraged to increase blood flow in the leg.

- Infection Prevention – Intravenous antibiotics will usually be given for 48 hours in the post-operative period, sometimes followed by oral antibiotics.

A significant number of patients subsequently elect to be transferred to an inpatient rehabilitation hospital to undertake early supervised physiotherapy and hydrotherapy. This is particularly useful for those patients who live alone.

Other patients choose to go directly home, but it is often safer to arrange for a friend, family member or caregiver to provide some help at home in the early stages. An outpatient programme of exercises and hydrotherapy can still be arranged prior to your initial hospital discharge. You will continue to wear the long compression (TED) stockings for 6 weeks, thinning (Clexane) injections are typically used for a total of 4 weeks from surgery (although those with higher risk may need a longer treatment phase), ice is used regularly to control swelling, a pain management plan is created for each patient prior to discharge, and advice is provided for planned suture removal.

Most importantly, if any concerns develop, particularly if there are any developing signs of blood clots or infection, you MUST contact A/Prof Woodgate as soon as possible.