INTRODUCTION

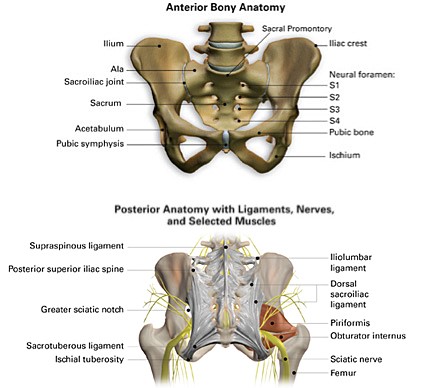

The sacroiliac (SI) joints are located in the pelvis. They link the iliac bones of the right and left sides of the pelvis to the sacrum (lowest part of the spine above the coccyx – tailbone). These joints transfer weight and forces between the upper body and legs. Only small amounts of motion occur in any direction, though there is some disagreement as to the exact amount. In normal people, it would be imperceptible to examination. Even specific Xrays will often reveal less than 1mm movements. Each joint has an approximate surface area of 17.5 square cm. The main articular (joint) component is the more anterior and lower part, and is variably described as “ear-shaped” or “like a boomerang”. The powerful ligaments lie in the upper posterior part, where the bones are not in contact.

Anterior and Posterior Bony Anatomy Sacroiliac Joint

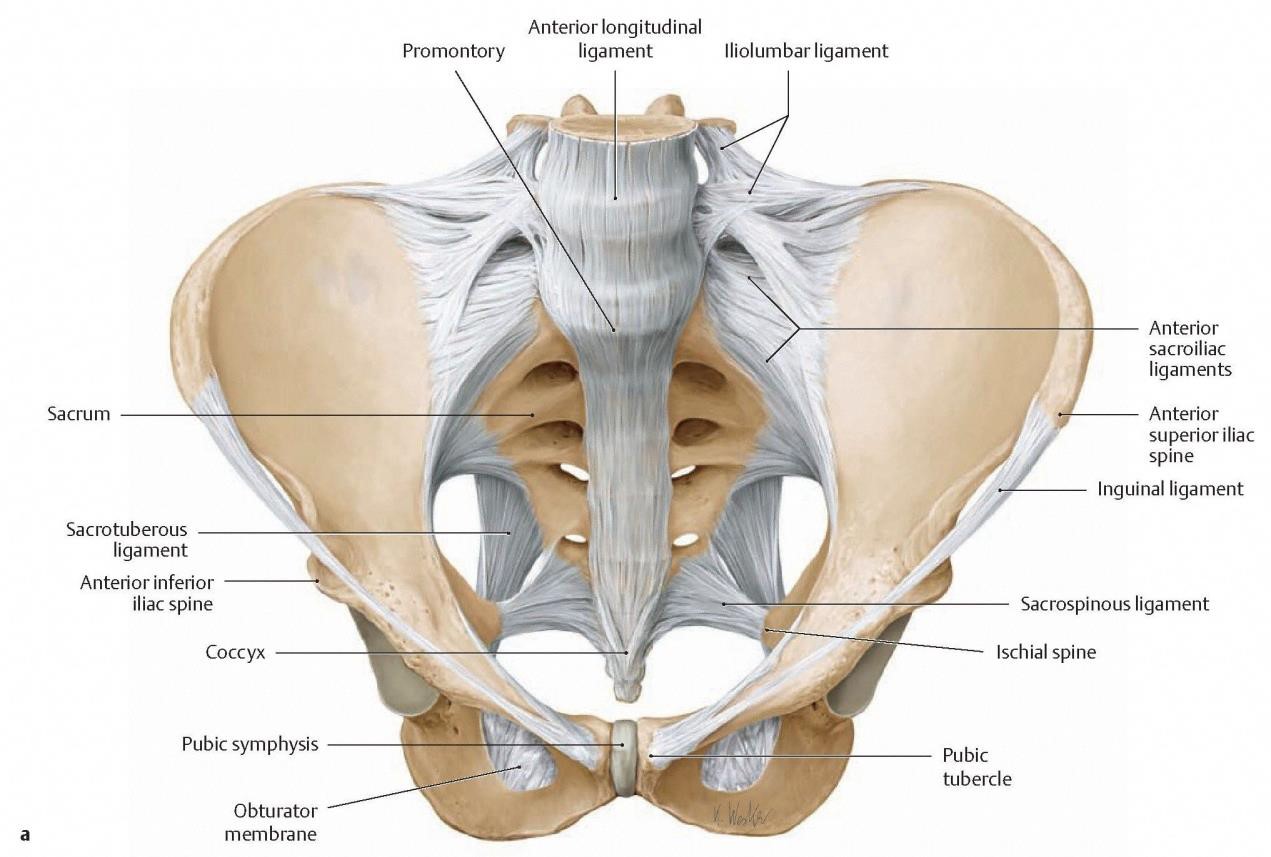

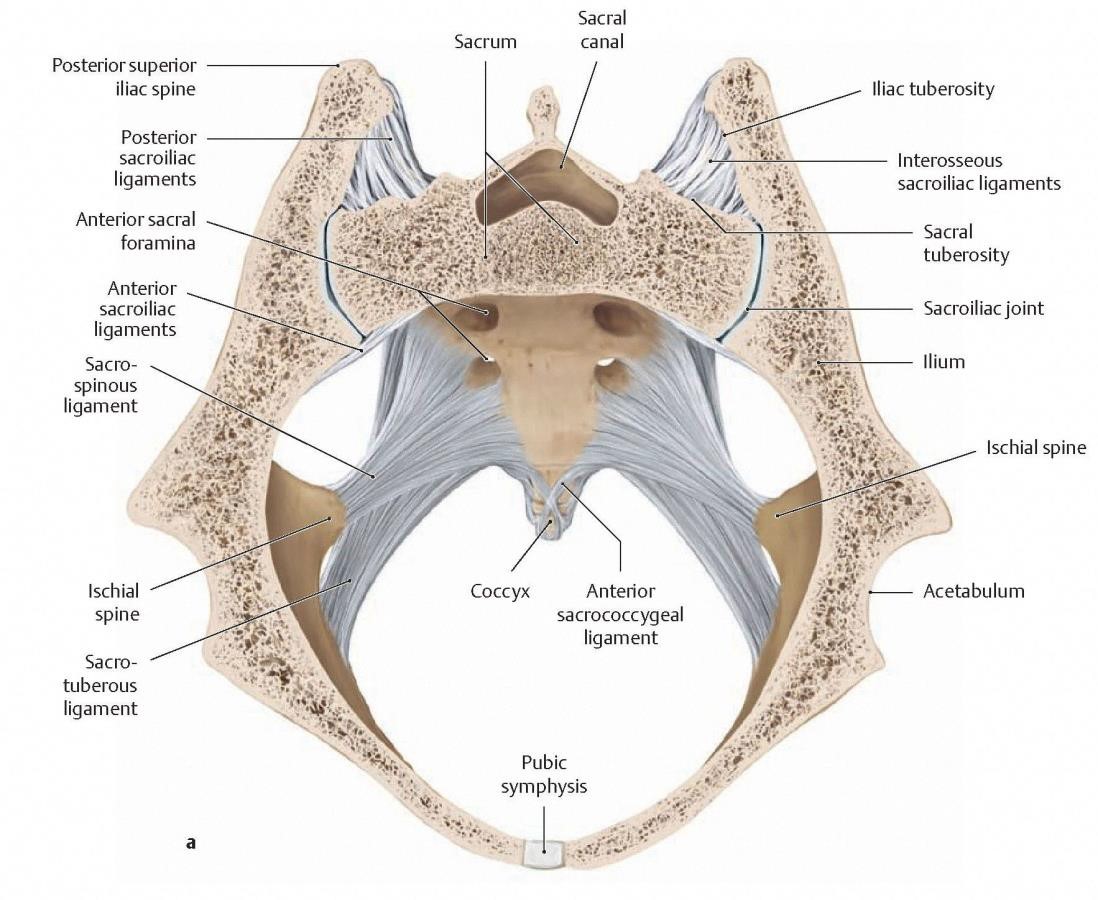

The paired (right and left) sacroiliac joints are in fact true diarthrodial (mobile) joints, characterized by matching articular (joint) surfaces, which are separated by a joint space containing synovial fluid, and are enveloped by a fibrous capsule. Rather than being smooth, the articular surfaces have many ridges and depressions that minimize movement and enhance stability. Several myofascial structures influence movement and stability, most notably the latissimus dorsi muscle (via the thoracolumbar fascia) and gluteus maximus.

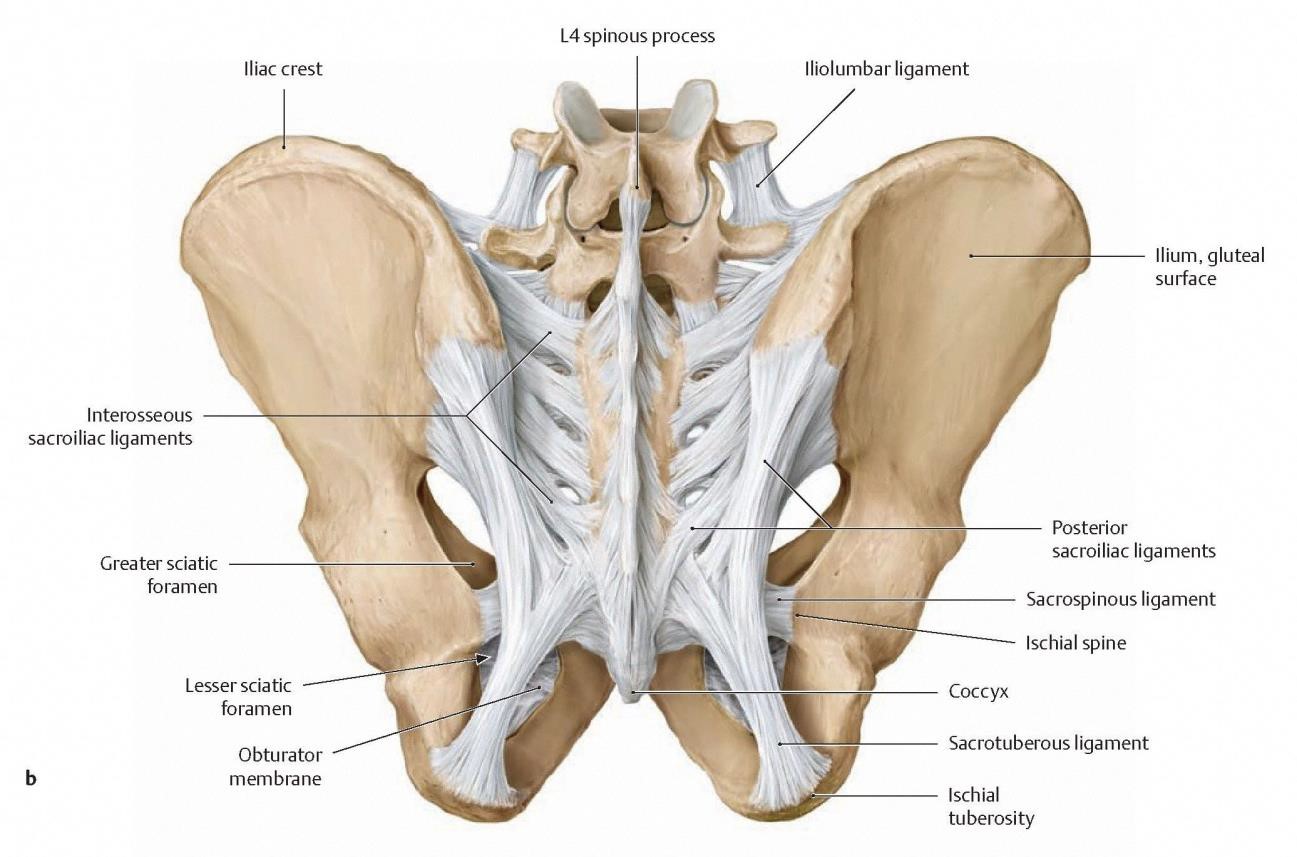

The primary stability however is attributed to the many adjacent strong ligaments.

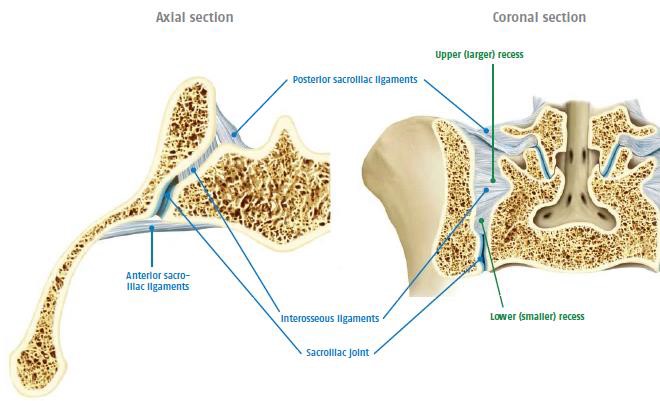

The anterior joint capsule is relatively thin and commonly has defects that will allow fluid substances injected into the joint to leak out. The anterior sacroiliac ligament is relatively weak and thin, and represents the caudal (lower) extension of the iliolumbar ligament. During arthrography studies, where contrast fluid is injected into the joint, contrast leakage occurred into the ventral (anterior) region in close proximity to the lumbosacral plexus – contrast was also seen to leak posteriorly around the dorsal sacral foramina – this may be one of the mechanisms for referred neuropathic pain.

The interosseous sacroiliac ligament is the strongest of the supporting ligaments, and has an extensive bony origin and overall volume. It fills the dorsal (posterior) and cephalad (superior) spaces of the extra-articular part of the joint (outside the synovial component of the joint). It provides the major multidirectional structural stability.

The dorsal (posterior) sacroiliac ligaments extend from the median and lateral sacral crests and run diagonally in a superior direction across the sacral recess, and attach to the ilium, including the posterior superior iliac spine. Overlying the dorsal ligaments and arising from them are the erector spinae (multifidus group – it has a strong muscular aponeurosis fused to the thoracolumbar fascia) muscle and the posterior part of the gluteus maximus origin. These muscles act through their attachment to produce sacroiliac joint movement, which is described as nutation and counter-nutation.

Sacroiliac Joint Movement

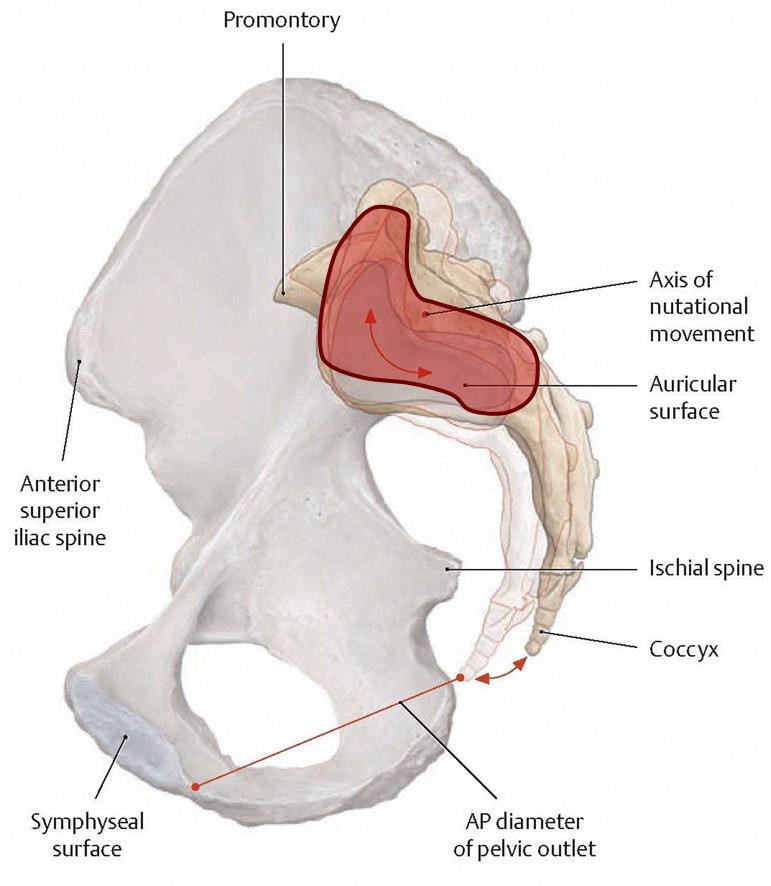

Studies have shown that sacroiliac joint motion is a combination of simultaneous sagittal (lateral) plane rotation and translation.

Nutation occurs with lumbosacral extension – the superior part of the sacrum moves forward whilst the lower inferior part rotates backwards. Counter-nutation occurs with lumbosacral flexion – the superior part of the sacrum moves backward whilst the lower part rotates forwards. There remains significant debate and controversy about the position of the true axis of this rotation, the extent of rotation (which may be as little as 0.5 degrees on a recent study), and the amount of translational movement in other planes.

Practically, on a plain weight-bearing Xray of the pelvis, the movement will be virtually undetectable in a normal (undamaged or non-pathological) pelvis, i.e. it is less than 1mm at the anterior pubic symphysis, which is the furthest bony point from the sacroiliac joint.

Sacroiliac Joint Nerve supply

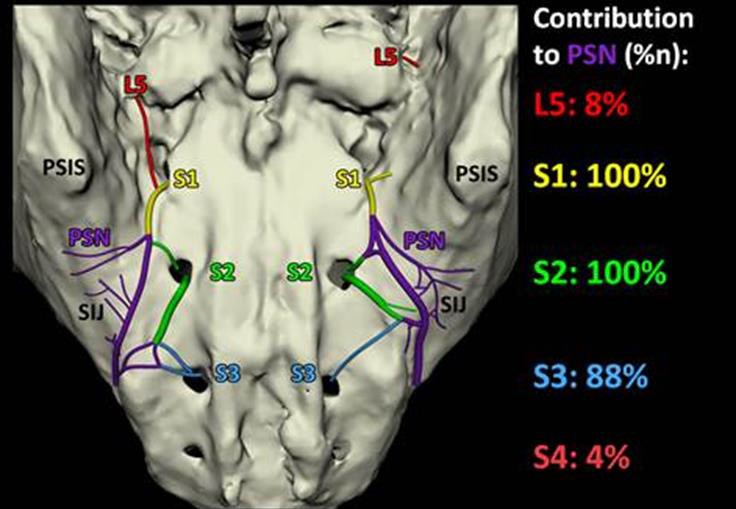

The sacroiliac joints and sacrum have a segmental innervation from L2-S4 nerves, predominantly by the S1 and S2 nerves, with the posterior part more supplied by the lateral branches of the L4-S3 dorsal rami, and the anterior joint innervated by L2-S2. This rich innervation probably explains why sacral nerve blocks and RFA (Radiofrequency ablation) rarely completely relieves pain induced from the sacroiliac joint.

The insufficient capsular envelope around the joint (particularly being thin or deficient anteriorly) may explain the mechanism or pathway that inflammatory pain mediators can leak through onto the neural structures. This also likely accounts for the radicular leg pain (“sciatica”) commonly seen, especially in the distribution of the main L5 nerve, which lies 10-12mm anterior to the joint.

Yellow arrow pointing to L5 nerve

SACROILIAC FUNCTION AND BIOMECHANICS

Male patients typically tend to have translational motion of the sacroiliac joint, whilst females have more rotational movement. In females, the ligaments are weaker, allowing the increased mobility necessary for childbirth. The sacroiliac joints are the connecting link between the lower limbs and the axial skeleton. It has been concluded from multiple studies that the main function of the joint is stability, allowing transmission and dissipation of truncal load to the extremities.

Interestingly, biomechanical studies have found that due to the due to their distinct anatomy and location, the sacroiliac joints can only withstand 50% of the torsional load and 5% of the axial compression load compared with the lumbar spine, which may result in injury.

The joint has several unique anatomic characteristics that can render it vulnerable to abnormal stress or strain. The sacroiliac joint is the largest axial joint in the body, with an average surface area of 17.5cm2. Only the anterior third of the interface between the sacrum and the ilium is a true synovial joint, with the rest composed of a complex set of ligamentous connections functioning to limit motion in all planes of movement. The joint has a vertical orientation resulting in more shearing forces, and these forces are particularly concentrated in the limited anterior synovial area. The sacral articular cartilage is twice as thick as the iliac cartilage, whilst the subchondral iliac end-plate bone is 50% thicker than that of the sacrum. This may explain the reason that degenerative change on the sacral side may lag by 10-20 years behind those affecting the iliac surface.