The sacroiliac joint is primarily involved in 15-30% of patients presenting with low back/leg pain. It has a significant impact on quality of life, with patients have sacroiliac pain being more severely affected than patients with chronic obstructive lung disease or mild heart failure, and being equivalent to that of patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis. In the United States, a study of the economic burden of conservative care for the commercial payer population of sacroiliac disease patients was estimated to be a 3-year cost of $1.6 billion per 100,000 covered lives. This has likely contributed to the increase in emphasis more recently to procedural-based management for sacroiliac pain.

Regardless, the initial management of sacroiliac dysfunction will be a conservative (non-surgical) programme, and those patients that fail to respond are then considered for surgical intervention.

CONSERVATIVE (NON-SURGICAL) MANAGEMENT

The goals of non-surgical treatment are based on elimination of any pain generators, restoration of hip and lumbopelvic mechanics, and restoration of patient function. Multiple modalities are advocated to aggressively treat the condition.

Medical management is used as an augment to the more physically based therapies. The mainstay is regular simple analgesia with Paracetamol taken regularly (up to a maximum of 4g per day, which is the equivalent of 8x500mg normal Paracetamol tablets, or 6x665mg Panadol Osteo tablets). The use of NSAIDS (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), such as Nurofen or Naprosyn, can help relieve inflammation and provide some additional analgesia. In more severe or acute cases, narcotic (opioid) medication and/or neuropathic medication may be prescribed.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) can be tried as a minimal-risk non-invasive modality.

Bracing Treatment

A pelvic/sacral belt can limit sacroiliac joint motion and provide some relief from acute pain. The compressive belt reduces the shear force across the joint in addition to reducing overload stress across the muscles surrounding the joint. Ideally the belt should not be used in the long term to prevent dependence and muscular weakness resulting from core muscle atrophy. A pelvic belt may have particular value in pregnancy-associated sacroiliac pain where medical therapy and injections may be limited or contraindicated.

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy is most beneficial in the early acute phase of pain to address deficiencies in strength, proprioception (joint position sense), and flexibility. Strengthening of pelvic and trunk core muscles is particularly beneficial due to the dynamic stabilising via the fascial attachment of muscles to the sacroiliac joint complex. However, certain exercises should be avoided as they are likely to overload the joint and provoke pain. A/Prof Woodgate recommends that hip external rotation or “clam” exercises should not be performed, and straight leg lifts should also be avoided to prevent strain on the sacroiliac joint.

Intra-Articular Injection

Sacroiliac joint injections with local anaesthetic and steroids have the strongest evidence supporting their use, but injection done without imaging control has been shown to be inconsistent. It is a requirement for effective injection to use fluoroscopy (X-ray imaging) or CT scans to confirm correct intraarticular positioning. A/Prof Woodgate also prefers to have arthrogram images to confirm localisation, which is best seen on CT images. The arthrogram will also demonstrate areas of capsular or ligamentous deficiency.

Intra-articular injection is not an isolated treatment or cure. It is initially a diagnostic tool to further confirm the provisional diagnosis that was based on the history, clinical examination, and imaging studies. If the local anaesthetic component injected gives significant relief of symptoms in the first 4-6 hours, this is considered a positive response. Not all patients necessarily obtain any significant benefit from the steroid component, which may take 5-10 days to have any response.

Prolotherapy

Prolotherapy involves a programme of injections (usually 3 injections done 3-4 weeks apart) of a glucose-based solution (typically 50% Dextrose) into the sacroiliac joint. To perform this injection properly usually requires CT scan control, combined with an arthrogram (the injection of dye into the joint) to confirm correct positioning. The injection creates an inflammatory response that results in fibroblast migration and increased ligamentous and capsular scarring. It is postulated that this extra capsular and ligament scarring result in less movement or hypermobility of the joint, which then causes less irritation to the rich nervous plexus surrounding the joint, and therefore less pain.

Whilst some inject only the posterior fibroligamentous portion of the joint, A/Prof Woodgate prefers a significant part of the injection to be intra-articular in the synovial part of the joint – this allows some of the injection to also travel and/or leak anteriorly, which further inflames and scars the joint or ligaments.

Some have considered this is of most benefit in patients with ligamentous laxity and sacroiliac instability. However, the experience of A/Prof Woodgate suggests that those patients who do have a true ligament laxity syndrome, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, may only obtain temporary benefit, as the capsule and ligaments will again inevitably stretch.

Experience over many years has shown that about 75-80% of patients report some benefit from the prolotherapy injection programme. Further, it is felt that if 3 injections fail to give adequate benefit, that repeat prolotherapy is unlikely to give further improvement (though A/Prof Woodgate will occasionally suggest this in patients with significant pain who may not be suitable for subsequent surgical intervention due to co-morbidities). It does appear that those patients that do respond well early, do seem to have a lasting improvement, though interestingly the functional flamingo X-rays may still show a small amount of persistent instability.

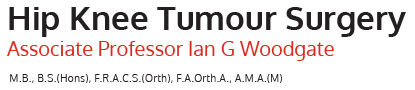

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA)

Radiofrequency ablation (also known as radiofrequency neurotomy) uses the heat generated by radio waves to target specific nerves and temporarily turn off their ability to transmit pain signals. Needles are inserted through the skin using image guidance to deliver the radio waves to the specific nerves in the reference area. The theory is that this technique will provide longer-lasting pain relief. The limitations in effectiveness are due to the complex innervation of the sacroiliac joint, as typically only the posterior nerve branches can be relatively easily accessed. Overall, the efficacy is thus limited by the inability to denervate the anterior and superior nerve structures, and by the inevitable slow recovery or regeneration of the posterior nerves over a 3-6 month period. Regardless, some patients do report benefit, and in these cases, it may be worthwhile repeating as symptoms return, especially as it is a safe percutaneous procedure with low complication rates. The best results have been seen in patients who have undergone a pre-ablation successful nerve block.

kogleckmtc.com

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT (Sacroiliac arthrodesis)

Surgical intervention is indicated for those patients who fail to adequately respond to a conservative (non-surgical) programme. Practically, this really means a group of 20-25% of patients who have proven sacroiliac joint dysfunction or instability that have obtained inadequate relief of symptoms.

The use of arthrodesis (fusion) has been described for surgical stabilisation of the sacroiliac joint as a method of pain relief/reduction since 1920. The rationale for sacroiliac arthrodesis is similar to fusion of other joints in the body – pain that is created from abnormal or excessive movement of a joint with inflammation or irritation of adjacent nerves can be relieved through removal of movement by obliteration of the joint space.

Arthrodesis must also be clearly differentiated from isolated screw fixation, as is utilised in the acute pelvic trauma/fracture/dislocation situation, as the later technique stabilises the acutely injured area but does not involve specific destruction or obliteration of the joint surfaces, nor does it involve insertion of bone graft to encourage fusion. If simple screw fixation where to be used in the chronic situation encountered in sacroiliac dysfunction or instability, it would almost certainly fail due to the lack of bone graft. Similarly, simple screw fixation in a salvage situation is doomed to mechanical failure unless formal fusion with bone graft is added.

Multiple different techniques have been reported for sacroiliac joint arthrodesis, but they can essentially be divided into 2 main groups:

- Open arthrodesis

- Minimally-invasive (or percutaneous) arthrodesis.

Open Sacroiliac Arthrodesis

Whilst open sacroiliac arthrodesis has been described using an anterior or a posterior approach, A/Prof Woodgate prefers the anterior approach as it provides direct visualisation and access to the superior and ventral parts of the synovial (true) joint without any significant disruption of the strong posterior ligaments in the extra-articular portion of the joint. It is especially indicated and useful in patients with aberrant or abnormal sacral anatomy (often from previous trauma), sacral dysmorphism, patients with significant pelvic instability, significant ligament laxity syndrome, or in cases of non-union or revision surgery. There have been reports in the literature of notable complications with damage to significant neurovascular structures including the major L5 and S1 ventral nerve roots (which subsequently form part of the sciatic nerve) as well as damage to iliac vessels and other structures that pass through the greater sciatic notch. A/Prof Woodgate has not seen these issues, and in fact in over 250 open cases, there has been no major nerve or vessel injuries.

A/Prof Woodgate’s Technique for Open Sacroiliac Arthrodesis

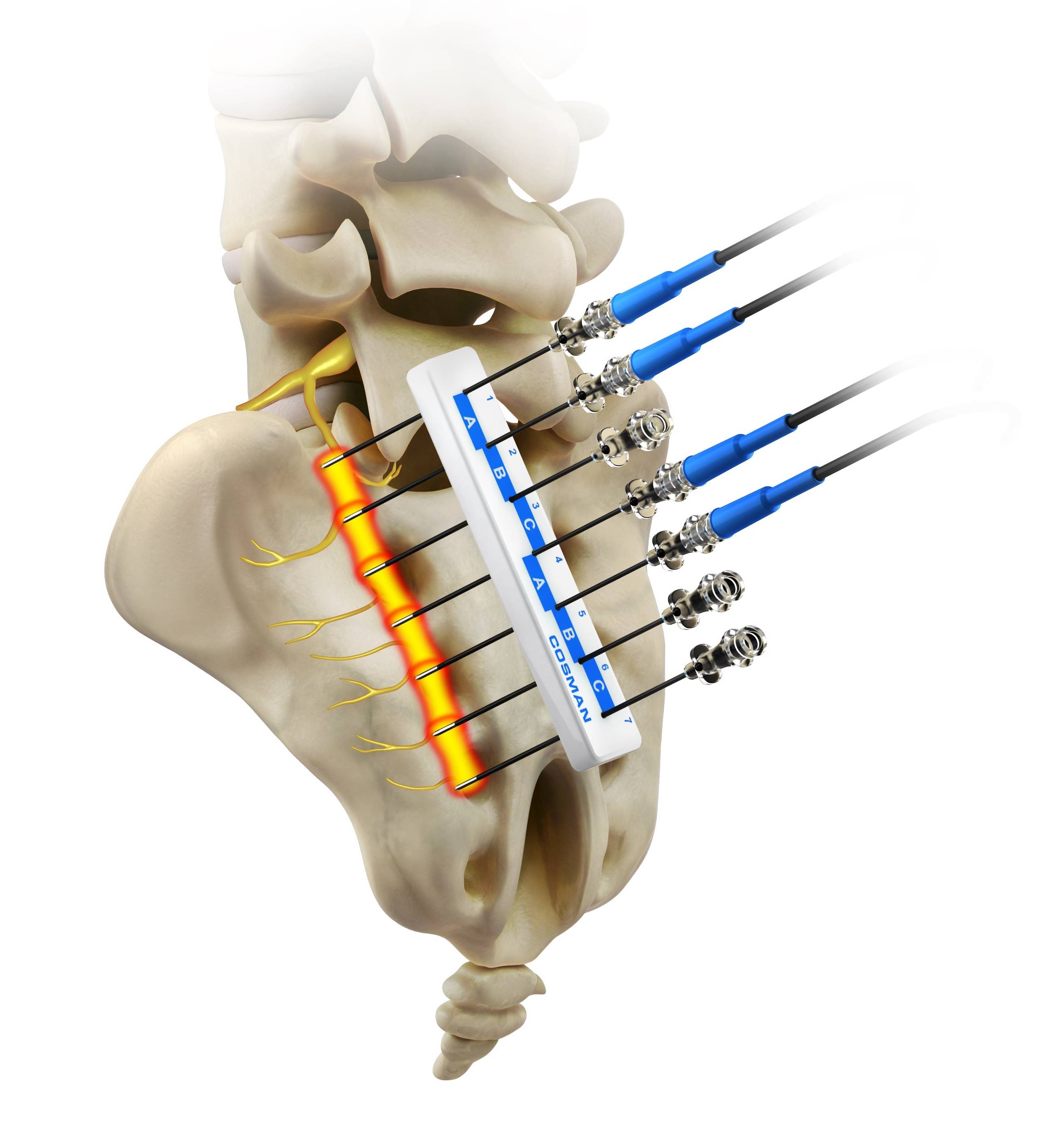

The surgery is performed under combined spinal and general anaesthesia. Routine combination intravenous antibiotics are used (currently Vancomycin and Ciprofloxacin) that will run for 48 hours. The patient is positioned in a “floppy lateral” position lying on a beanbag on the operating table. Following routine skin preparation with antiseptic solution, sterile drapes are applied to seal off the operating field. An incision of 14-16cm is made curving along the line of the iliac crest, and carried down through the subcutaneous fat layer to the bony crest and abdominal muscles. The lumbar triangle of Petit (formed by the junctions of the posterior margin of the external oblique muscle, the anterior margin of the latissimus dorsi muscle, and the superior part of the iliac crest) is identified and used as the landmark to gain access to the pelvic retroperitoneal space.

Pinterest.com

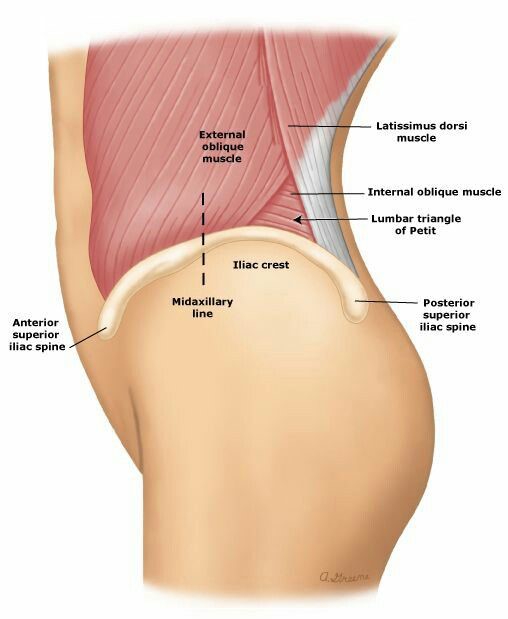

This creates a virtually bloodless approach to elevate the abdominal wall muscles from the iliac crest as the exposure is progressed anteriorly almost to the anterior superior iliac spine, being careful to preserve the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh at the anterior extent. The table is then tilted to allow the patient to slightly roll backwards into almost a supine position. After positioning self-retaining retractors to keep the elevated abdominal wall muscles anterior, the iliacus muscle on the inner table of the iliac bone is then elevated from the crest and mobilised anteriorly and medially. Approximately 1cm lateral to the iliac crest is a nutrient blood vessel that will require cauterisation. Immediately adjacent to the sacroiliac joint the iliacus muscle can be quite adherent to the anterior sacroiliac ligaments. Once this area is freed, the subperiosteal mobilisation can further progress for 1-5-2cm across the superior part of the sacrum. Inferiorly a blunt retractor will protect all neurovascular structures running in the greater sciatic notch. More superior and posterior, care is required not to inadvertently cut the iliolumbar vessels. An excellent view is obtained of the sacroiliac joint, which can then be fully debrided to remove any remaining cartilage with a combination of a curette, followed by the use of a high-speed burr.

The joint is then packed with a combination of local bone graft (autograft) and combined with additional synthetic bone graft substitute to fill any voids within the joint. Two compression plates are then applied, using a 2-hole AO Barrack dynamic compression plate inferiorly with two 6.5mm long (32mm) thread compression screws, and supplemented with a superior 5-hole 3.5mm AO pelvic reconstruction plate with four 4mm cancellous screws. These two plates are almost positioned at 90 degrees to each other, and provide rigid initial compression and fixation. Supplemental synthetic graft is then placed above, between, and below the plates and spanning the sacroiliac joint.

The iliacus muscle is then repaired over the top of the plates and bone graft. A TAP (transversus abdominal plane) block catheter is inserted and brought out through the skin of the anterior abdomen, for subsequent connection to a Painbuster local anaesthetic catheter. The abdominal wall is repaired to the iliac crest with multiple transosseous non-absorbable sutures drilled through the bone, and supplemented with a continuous absorbable suture. A drain is inserted and the more superficial wound is closed in layers. Sterile pressure dressings are applied. The general anaesthetic is then reversed, and the patient is transferred to a trolley, and subsequently moved to the Recovery Unit for early close observation until the patient is fully awake. An X-ray is performed in Recovery to confirm the expected position of the plates.

The average surgical time for this procedure is 90 minutes (range 73-145 minutes), with an average intra-operative and post-operative blood loss of less than 100mls.

Post-Operative Period after Open Sacroiliac Arthrodesis

Patients rest in bed for 48 hours post surgery to allow the wound to settle, and regular ice is helpful. A triangular (abduction) pillow is placed between the legs and will continue to be used for 6 weeks. Diet and food are restricted until there is return of bowel sounds and the patient passes flatus, to prevent the risks associated with vomiting. Routine DVT thromboprophylaxis is utilised, including short TED compression stockings (used for 6 weeks), sequential calf compressors are used during the hospital stay, Clexane (low molecular weight Heparin) injections are given once daily, for one month, and a Duplex ultrasound scan is performed on day 5-6 to confirm there is no clots. This is a painful procedure initially, and the Painbuster local anaesthetic device certainly helps, but to this is added regular Paracetamol as well as the use of a PCA (Patient Controlled Analgesia), which provides intravenous narcotic at the push of a button managed by the patient. The PCA typically runs for 3 days, and then the patient is transitioned to an oral analgesia programme.

On day 3, the drain, Painbuster, PCA and the intravenous cannula are removed, and the patient begins mobilising with the physiotherapist. There is a restriction to 50% partial weight-bearing for the first 6 weeks, and then to 75% weight-bearing in the second 6 weeks (i.e. restricted for 3 months), to allow for early bony fusion. The indwelling urinary catheter is removed on day 4. Most patients are transferred to rehabilitation on day 6, especially to undergo a gentle hydrotherapy programme and to progress safety with the restricted weight-bearing with crutches or a small frame. Certain movements are also limited, and in particular there should be no straight leg lifts, no active abduction (moving the leg to the side), and no hip external rotation for at least 6 weeks or until approved by A/Prof Woodgate. Any Nylon skin wound sutures are removed around day 12. The wound should not be immersed in water without a waterproof dressing for 6 weeks. Any strong oral analgesia is slowly decreased over a 3-month period. Regular follow-up review is undertaken with A/Prof Woodgate in his rooms, initially at 6 weeks post surgery.

CompIications of Open Sacroiliac Arthrodesis

The complication rate following open sacroiliac arthrodesis is very low in over 270 open cases performed by A/Prof Woodgate. Major medical complications such as heart attack or stroke have not occurred.

Possible risks and complications associated with open sacroiliac arthrodesis surgery include:

-

Infection – This may occur in the superficial wound or deep around the joint and hardware. It may happen while in the hospital or after you go home. Only 2 minor superficial infections in the wound area have been seen in the series of 270+ open cases of A/Prof Woodgate, and both settled promptly with oral antibiotic therapy only, and did not require readmission to hospital or further surgical intervention. A solitary deep infection only has occurred in this large series of 270+ cases, which subsequently required open washout and admission for antibiotics, though the outcome was positive progressing to healing and subsequent fusion (a clear source of this deep infection was identified and separately addressed). In this series, the true incidence of significant deep infection is currently 0.37%.

-

Blood clots (deep vein thrombosis) - In all 270+ open cases to date, only one calf DVT has been identified (which subsequently resolved with treatment), and there have been no pulmonary emboli. The prevention program, which includes lower leg exercises to increase circulation, short below-knee compression (TED) stockings, calf compressors, early mobilisation, and medication to thin your blood (Clexane injections), is important. A Duplex (ultrasound) scan of the lower leg veins on day 5 or 6 post-surgery is required to look for any signs of DVT formation.

- Loosening and implant wear – In the early post-operative period, a restriction on certain activities and a limitation on weight-bearing when mobilising is imperative. This allows adequate time for the bone graft placed within the joint and fusion area to begin healing and incorporating. In some cases, there can be a failure of the hardware with either breakage of a plate or screw, or loosening of the hardware. In over 270+ open cases in the series of A/Prof Woodgate, there have been only 3 plates that have broken (all being the smaller 3.5mm reconstruction plate – in these cases, the thicker Barrack plate was solid and fusion progressed unremarkably). In one case only, both plates and screws loosened (this was in a patient who had previously undergone whole pelvic radiation for cancer – the plates did not require removal as they were under the iliacus muscle and caused no irritation on any adjacent structures).

-

Failure of fusion – In the 270+ cases of open arthrodesis performed by A/Prof Woodgate, there has been only one case that has failed to progress to fusion – this is the patient noted above who had undergone whole pelvic radiotherapy for cancer prior to the fusion procedure, and subsequently the hardware became loose. To date, no revision fusion has been performed for this patient (or any other in this series). All cases performed have serial X-ray or CT scans to monitor progression to fusion.

-

Nerve and blood vessel damage – This is uncommon, though some patients may report a persistent small area of numbness around the surgical wound and thigh in the distribution of the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh, and most have resolved spontaneously over 6 months (10 patients in the series have had persistent numbness, but none have needed intervention). Damage to the major (particularly the L5 nerve root) nerves is reported in the literature, though A/Prof Woodgate has seen no cases in his series. Similarly, there have been no vascular injuries in his series.

-

Blood transfusion for bleeding – With modern anaesthetic and surgical techniques, and as noted above there being an average blood loss both intra-operative and post-operative totaling less than 100mls, blood transfusion has not been needed for any case in A/Prof Woodgate’s series.

-

Wound/Incisional Hernia – This complication is related to failure of the abdominal wall muscle repair to the iliac crest, which results in a deficiency through which abdominal or pelvic contents may bulge. A/Prof would has had 3 cases where the muscle repair failed – all occurred early in the series when at that stage only absorbable sutures where used for the muscle repair. Since the change to using non-absorbable sutures drilled through the bone of the iliac crest, no case has occurred. These three cases required revision abdominal wall repairs.

-

Continued pain - A small number of patients continue to have some pain after an open sacroiliac arthrodesis. The commonest cause is pain that can be transmitted from the opposite side sacroiliac joint, though other sites of referred pain may include the lumbar region and hip, as well as intrapelvic pathology. This complication is rare and sometimes a clear cause cannot be found. The vast majority of patients experience excellent pain relief and improvement following this surgery.

Percutaneous Sacroiliac Arthrodesis (Minimally Invasive)

Proposed advantages of the minimally invasive approaches that have been developed more recently include a shorter hospital stay, decrease limitation of the post-operative weight-bearing, decrease in morbidity related to blood loss, smaller wound incisions with theoretical decrease in rate of surgical site infection, and less surgical pain.

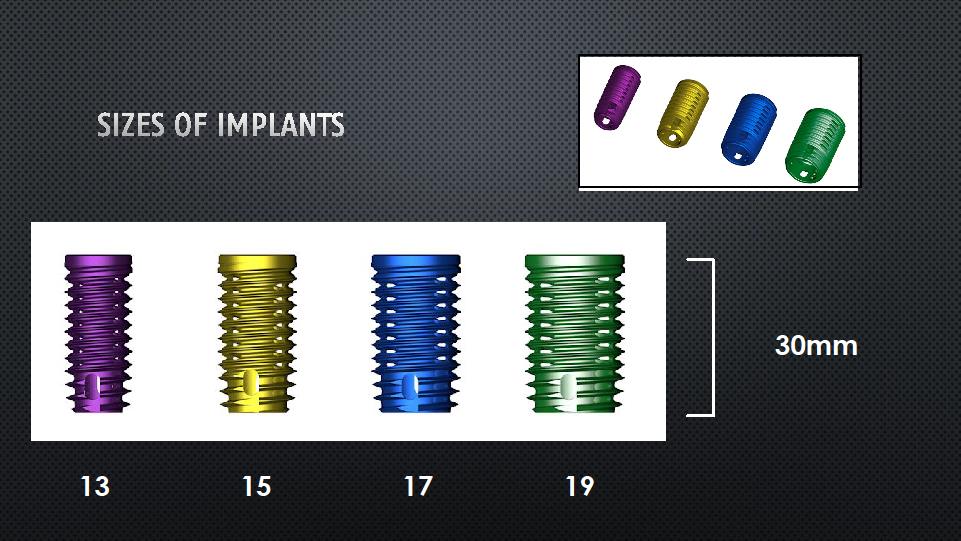

Currently, there are 3 different types or groups of minimally invasive sacroiliac arthrodesis implants available in Australia:

-

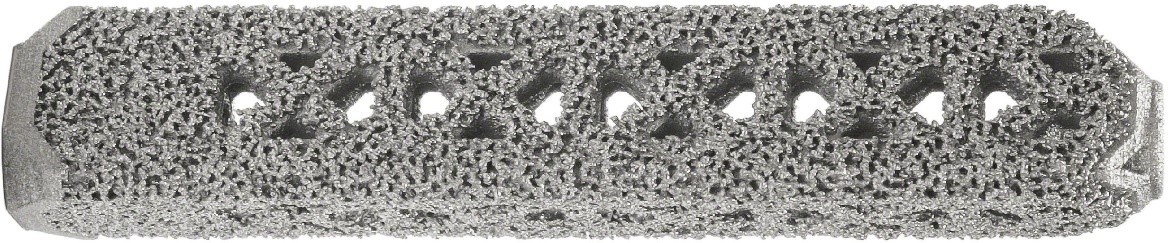

The direct lateral fixation systems, of which the best known is the iFuse of iFuse 3D system (designed by SI-Bone, and distributed in Australia by Device Technologies). The original iFuse implant was a solid triangular cannulated titanium rod. The newer iFuse 3D that A/Prof Woodgate uses has multiple ingrowth recesses.

-

The DIANA system (Distraction Interference Arthrodesis with Neurovascular Anticipation), which is implanted via a posterior approach (designed and marketed by Signus).

-

The Rialto system, inserted via a percutaneous posterolateral approach (from Medtronic).

Of these 3 types, A/Prof Woodgate only uses the iFuse 3D and the DIANA systems. He has specifically decided not to use the Rialto system as he believes that the implants do not provide adequate ingrowth or ongrowth potential, and that the insertion technique is at an oblique angle to the forces across the sacroiliac joint, which is not conducive to mechanical loading that will result in fusion.

A/Prof Woodgate’s Technique for iFuse 3D Sacroiliac Arthrodesis (minimally invasive)

The procedure is performed under general anaesthetic (which may be combined with spinal anaesthesia in those patients with significant pre-operative pain management issues). Routine combination intravenous antibiotics are used (currently Vancomycin and Ciprofloxacin) that will run for 48 hours. The patient is positioned in a prone position lying on a normal operating table with small rolled-up towels used as bolsters under the chest and pelvis. Care is taken to ensure the patient is placed on the table to allow adequate access for the image intensifier (X-ray) to provide all images necessary for the image-guided insertion. Skin markings are made that will also aid in the insertion technique. Following routine skin preparation with antiseptic solution, sterile drapes are applied to seal off the operating field. A 3-4cm incision is made on the lateral side of the buttock, and dissection carried down through the fat layer as far as the fascia overlying the gluteal muscles. A pin is placed through the muscle under X-ray guidance and impacted though the iliac bone, across the sacroiliac joint, and into the sacrum. A blunt dissector is passed over the pin to gently spread the muscle fibres. A soft tissue protector is passed over the pin and through the muscles down to the lateral (outer) surface of the iliac bone. A length gauge is then used to measure the implant length. The pin sleeve is removed but the soft tissue protector and pin are retained. The cannulated drill is passed over the pin (inside the soft tissue protector) to just drill the lateral (outer) cortex of the ilium. The drill is carefully removed ensuring the pin and soft tissue protector do not come out. A cannulated stepped broach is then inserted over the pin (inside the soft tissue protector), and advanced under X-ray guidance in the appropriate orientation until the stepped teeth just cross through the sacroiliac joint into the sacrum. The broach is carefully removed leaving the pin and protector in place. The definitive iFuse 3D implant of the chosen size if prepared on a back table, where locally harvested autograft (the patient’s own bone is placed into the ingrowth spaces, and this is supplemented with synthetic bone graft material (currently A/Prof Woodgate uses Nanobone in this setting). The prepared implant is passed over the pin and through the soft tissue protector in the same orientation as the broach, and then impacted into position with X-ray control. Once finally seated, the implant will sit 2-5mm off the bone. The soft tissue protector is removed leaving the pin inside the implant. A parallel pin guide is positioned with the first pin in one hole, and X-ray will guide positioning of the guide for the second pin. Once the second pin is impacted, the parallel pin guide is removed. The sequential steps of blunt dissection, insertion of the soft tissue protector, length measurement, drilling, broach insertion, implant grafting, and implant impaction are repeated. The same sequence is also used for a third implant. Final positioning of the 3 implants is confirmed. All pins are removed. The wound is washed out with saline. The small fascia/muscle splits are sutured closed. Local anaesthetic is widely infiltrated. The wound is closed in layers and no drain is required. Sterile pressure dressings are applied. The general anaesthetic is then reversed, and the patient is transferred to a trolley, and subsequently moved to the Recovery Unit for early close observation until the patient is fully awake. An X-ray is performed in Recovery to confirm the expected position of the 3 iFuse implants.

The average surgical time for this procedure is 45-65 minutes (skin-to-skin time), with an average intra-operative and post-operative blood loss of less than 100mls.

SI-Bone

iFuse 3D implant

Post-Operative Period after iFuse 3D Sacroiliac Arthrodesis (minimally invasive)

Patients only rest in bed overnight, and mobilisation commences on day 1 with 50% partial weight-bearing. Regular ice is applied to the buttock region to decrease any post-surgical swelling. A triangular (abduction) pillow is not required after this procedure. Diet and food are restricted until there is return of bowel sounds and the patient passes flatus, to prevent the risks associated with vomiting, but most patients can tolerate a light meal on the same evening of the surgery. Routine DVT thromboprophylaxis is utilised, including short TED compression stockings (used for 6 weeks), sequential calf compressors are used during the hospital stay, and Clexane (low molecular weight Heparin) injections are given once daily (usually only during the period of hospitalisation), though this may continue for longer of the patient is flying or has a past history of clots. Regular Paracetamol is prescribed for pain, along with anti-inflammatory medication (if it can be tolerated) as well as the use of a PCA (Patient Controlled Analgesia), which provides intravenous narcotic at the push of a button managed by the patient. The PCA typically runs for 2 days only, and then the patient is transitioned to an oral analgesia programme.

On day 2, the PCA, the intravenous cannula, and the indwelling urinary catheter are removed. There is a restriction to 50% partial weight-bearing for the first 3 weeks, and then to 75% weight-bearing in the second 3 weeks (i.e. restricted for 6 weeks), to allow for early bony fusion. Most patients are discharged directly home on day 3 or 4. Certain movements are limited, and in particular there should be no straight leg lifts, and no hip external rotation for at least 6 weeks or until approved by A/Prof Woodgate. Any Nylon skin wound sutures are removed around day 12. The wound should not be immersed in water without a waterproof dressing for 6 weeks. Any strong oral analgesia is slowly weaned over a 3-6 week period. Regular follow-up review is undertaken with A/Prof Woodgate in his rooms, initially at 6 weeks post surgery.

CompIications after iFuse 3D Sacroiliac Arthrodesis (minimally invasive)

The complication rate following iFuse3D minimally invasive sacroiliac arthrodesis is very low. Major medical complications such as heart attack or stroke have not occurred.

Possible risks and complications associated with iFuse 3D minimally invasive sacroiliac arthrodesis surgery include:

-

Infection

-

Blood clots (deep vein thrombosis)

-

Loosening

-

Failure of fusion

-

Nerve and blood vessel damage – This is uncommon, though some literature papers have reported injury to the superior gluteal artery in the buttock during implantation (A/Prof Woodgate has seen no cases in his series 30+ cases to date). Four patients have noted some sciatica-like symptoms including paraesthesia (feeling of “pins and needles”) radiating into the legs. All cases have settled spontaneously over a period of a few months without the need for intervention. No major nerve injuries have been seen.

-

Blood transfusion for bleeding

-

Continued pain

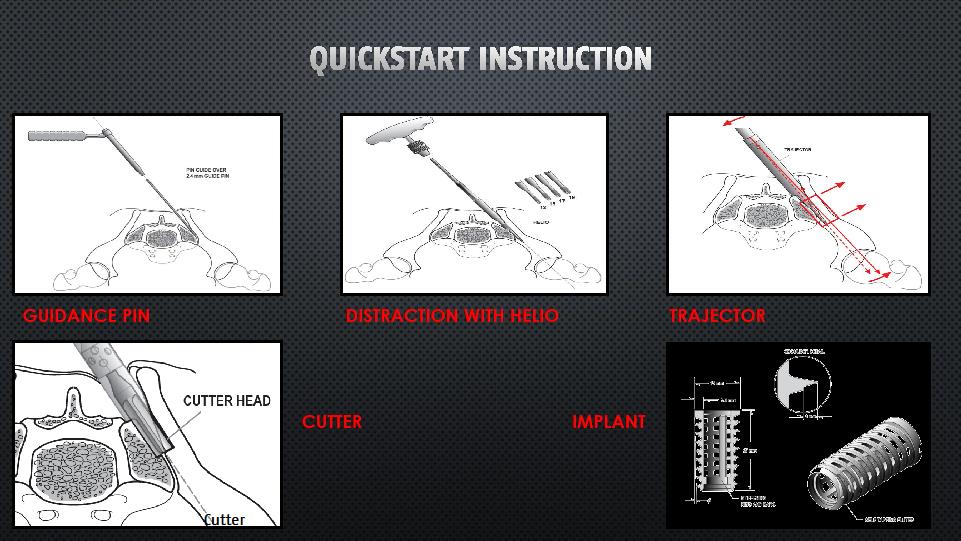

DIANA Sacroiliac Arthrodesis (minimally invasive)

Distraction Interference Arthrodesis with Neurovascular Anticipation is a relatively atraumatic and low-risk procedure that involves anchoring an interference implant (titanium alloy hollow screw) via a posterior access distally in the iliac bone. The more proximal and central part of the implant is located in the posterior extra-articular sacroiliac recess without affecting the true articular (joint) surfaces. The surgical access to this recess and the subsequent path of the instruments and implant follow the line of the iliac bone weight-bearing axis. The joint is distracted during the procedure, which relieves stresses on the true joint, though permanent fusion is achieved by the insertion of supplemental bone graft in both the extra-articular recess and inside the implant.

A/Prof Woodgate believes that the DIANA technique should NOT be used for patients with marked sacroiliac/pelvic instability (movement on flamingo weight-bearing X-rays >2-3mm), patients with ligament laxity syndromes, sacral dysplasia or dysmorphism (with abnormal shape to the posterior sacroiliac recesses), and for revision fusion for previous failed fixation.

Incomplete URL

A/Prof Woodgate’s Technique for DIANA Sacroiliac Arthrodesis (minimally invasive)

The procedure is performed under general anaesthetic. Routine combination intravenous antibiotics are used (currently Vancomycin and Ciprofloxacin) that will run for 48 hours. The patient is positioned in a prone position lying on a normal operating table with small rolled-up towels used as bolsters under the chest and pelvis. Care is taken to ensure the patient is placed on the table to allow adequate access for the image intensifier (X-ray) to provide all images necessary for the image-guided insertion. Skin markings are made that will also aid in the insertion technique. Following routine skin preparation with antiseptic solution, sterile drapes are applied to seal off the operating field. A posterior midline incision is made and carried down through the skin and subcutaneous fat layer to the thoracolumbar fascia. The fat is mobilised laterally over the fasci down to the posterior superior iliac spine and recess. The fascia is incised longitudinally approximately 1cm medial to the iliac bone, and dissection carried down to the posterior recess and sacrum. The upper and lower recess are then carefully opened and cleared of the ligaments until the posterior part of the synovial joint is visualised. Multiple small drill/burr holes are drilled in the medial side of the ilium and the lateral side of the sacrum in the recess to expose the medullary bone. The direction for the guide wire is then determined using imaging control, with the wire advanced into the ilium for about 2-5cm and position confirmed in multiple planes. The smallest helio (a cannulated threaded cone distractor) is passed over the wire, and larger size helios may be needed until there is firm seating. A trajectory is slid over the helio and impacted to maintain the distraction, and the helio is removed. The reamer of the same size to the final helio is then advanced to the desired depth. The reamer is removed and the definitive DIANA implanted is inserted into the recess via the guide wire, and rotated to the correct final position. The inserter, guide wire and trajectory are all removed. The internal section of the implant and the surrounding recess are filled with bone graft (usually allograft donor bone) and this graft is solidly compacted. The fascial layer is repaired. The wound is infiltrated with local anaesthetic, and then closed in layers over a suction drain. Sterile pressure dressings are applied. The general anaesthetic is then reversed, and the patient is transferred to a trolley, and subsequently moved to the Recovery Unit for early close observation until the patient is fully awake. An X-ray is performed in Recovery to confirm the expected position of the DIANA implant and bone graft.

www.signus

Incomplete URL

Post-Operative Period after DIANA Sacroiliac Arthrodesis (minimally invasive)

Patients only rest in bed overnight, and mobilisation commences on day 1 with 50% partial weight-bearing. Regular ice is applied to the back region to decrease any post-surgical swelling. A triangular (abduction) pillow is not required after this procedure. Diet and food are restricted until there is return of bowel sounds and the patient passes flatus, to prevent the risks associated with vomiting, but most patients can tolerate a light meal on the same evening of the surgery. Routine DVT thromboprophylaxis is utilised, including short TED compression stockings (used for 6 weeks), sequential calf compressors are used during the hospital stay, and Clexane (low molecular weight Heparin) injections are given once daily (usually only during the period of hospitalisation), though this may continue for longer of the patient is flying or has a past history of clots. Regular Paracetamol is prescribed for pain, along with anti-inflammatory medication (if it can be tolerated) as well as the use of a PCA (Patient Controlled Analgesia), which provides intravenous narcotic at the push of a button managed by the patient. The PCA typically runs for 2 days only, and then the patient is transitioned to an oral analgesia programme.

On day 2, the PCA, the intravenous cannula, and the indwelling urinary catheter are removed. There is a restriction to 50% partial weight-bearing for the first 3 weeks, and then to 75% weight-bearing in the second 3 weeks (i.e. restricted for 6 weeks), to allow for early bony fusion. Most patients are discharged directly home on day 3 or 4. Certain movements are limited, and in particular there should be no straight leg lifts, and no hip external rotation for at least 6 weeks or until approved by A/Prof Woodgate. Any Nylon skin wound sutures are removed around day 12. The wound should not be immersed in water without a waterproof dressing for 6 weeks. Any strong oral analgesia is slowly weaned over a 3-6 week period. Regular follow-up review is undertaken with A/Prof Woodgate in his rooms, initially at 6 weeks post surgery, at which time the initial post-operative X-ray is reviewed. At the 3-month visit, a CT scan is arranged.